Throughout the Postgraduate Certificate in Academic Practice (PGCAP), I was encouraged to use various models to facilitate my reflective practice (Gibbs, 1998; Moon, 2004). I found that when I first started to use such models this really helped me to focus my thoughts. It’s interesting to feel now that I’m relatively comfortable and confident in reflective writing, no longer feeling the need to explicitly structure my reflections using such models, although, now the questions are continuously in my head – progress I think!

Why AFL, when I’ve already done!

As a lifelong learner, I’ve never needed much of an excuse to participate in continuous professional development (CPD). However, my main motivation for joining the Assessment and feedback for learning (AFL) module after completing the PGCAP was strongly linked to my role as Academic Developer.

In the past, my role has been focused around supporting academic colleagues to use learning technologies to enhance their learning, teaching, and assessment practice, however more recently the role has changed into supporting learning and teaching in Higher Education (HE) more broadly including curriculum and assessment design. AFL, I felt was an excellent development opportunity to strengthen my ability to support colleagues in their academic practice as a whole, rather than specialising in Technology-Enhanced Learning (TEL).

Improving staff and student perceptions of assessment and feedback is a strategic goal identified locally within the University’s Learning and Teaching Strategy (University of Salford, 2011) aligned with national initiatives to transform assessment in UK HE (HEA, 2012), and therefore staff development in this area is high priority. By being part of the AFL community, and by listening to the ‘stories’ of colleagues from various contexts across the University, I can better understand the ‘feelings’ and ‘beliefs’ of my academic colleagues relating to their assessment and feedback practice.

Before joining the PGCAP as a ‘student’, I was part of the PGCAP programme team as tutor on the Application of Learning Technologies (ALT) module. Whilst I really enjoyed this aspect of my role, I valued the importance of experiencing the whole PGCAP learning journey myself, and of course achieving the PGCAP certification and Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy (FHEA). As the ALT module was my first tutoring experience, I was new to assessment and feedback practice, and felt that I had a lot to learn with regards to marking and providing feedback. Although I was often praised for being very helpful and constructive in my feedback, I did tend to give lots of it following submission (taking a long time to mark!), and that was an area I wanted to explore – how much feedback should I give, and when and how should I give it? I also experienced disparity between my marking and the marking of others within the module team (highlighted during moderation), and so wanted to explore – how much could I be subjective, how much and why did I need to ‘stick to a marking grid’, how specific does a marking grid or ‘rubric’ need to be? Although the PGCAP started to explore this, I felt there was more to learn, and hence my further interest in AFL.

AFL – the beginning

It seems not so long ago I was at the beginning of a new learning journey, starting as a small group all committed to spending the next three months sharing reflections, values, and experiences of assessment and feedback through a process of Problem-Based Learning (PBL). In some ways it was continuing the learning journey from the core module with familiar faces, which was ‘comforting’, although there were some new faces (including our tutor), which provided an element of ‘freshness’ and new insights. Having already experienced wonderful learning through the PGCAP, and passing the assessment, I felt more ‘relaxed’ about the assessment on AFL and able to focus more on the learning.

The first reflective task was the ‘feel-o-meter’; first defining themes relevant to my own learning journey (see post Back behind the wheel of AFL), and then deciding where I felt my current knowledge and experience was on the scale. It was encouraging to be able to map out my own ‘learning labels’ most relevant to my context.

AFL – the PBL journey

At the start, I was feeling relatively comfortable with learning through PBL, and quietly excited. Throughout the PGCAP I’d participated in various learning activities which adopted a PBL approach, and I’d started to reflect on how I may embed this into my own practice (see post Reflection 6/6 – Developing my PBL practice). Having the opportunity to experience as a ‘student’ first hand a PBL curriculum linked to assessment was a great opportunity to continue this reflection.

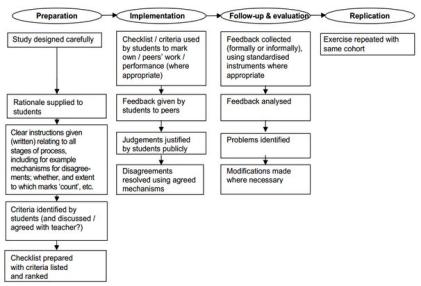

I felt my familiarity with PBL was an advantage, in that I wasn’t too concerned about learning in this way, and as my peers on the module were also continuing their PGCAP I made an assumption that we were all at the same place in terms of our understanding. However, reflecting now I don’t think this was the case. Half of the group, who were part of my core module cohort, may have recalled the brief introduction to PBL, however they may not have furthered their learning through reflections for assessment, and the other half of the group weren’t part of my previous cohort and therefore their core module syllabus may have been different. Also, my peers and I were from various contexts, and those from the science disciplines may have been less familiar with such approaches than those from health and/or educational disciplines. The unfamiliarity with PBL I felt contributed to a slow start from my PBL group, and looking back, perhaps I should have made more of an effort to guide my peers along a more structured PBL process (Barrett and Cashman, 2010), although I also didn’t want to appear the ‘know-all’ of the group.

7 Step PBL Process Guide (Barrett and Cashman, 2010)

Image source:http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/ucdtli0041.pdf

I realise that PBL can be adapted to suit the given context, and that sometimes it’s unnecessary to impose a tight structure. Although I agree that there should be flexibility and agreement between group members, I think that by proposing a model to work with, this would have helped everyone’s understanding. Perhaps an early PBL activity (not linked to assessment) or pre-induction readings/discussion would have helped. One of the case studies in A Practitioners’ Guide to Enquiry and Problem-based Learning (Barrett and Cashman, 2010) shows an example of effective staff development for lecturers in PBL, and is an excellent resource for practitioners. Whilst there’s no time for extensive staff development in a ten-week module, I’m sure more could be done to ensure the cohort is relatively comfortable with the process before starting the scenarios linked to assessment.

Of course, there are some aspects of this particular cohort that made the PBL scenarios particularly challenging. Best practice guidelines on PBL, or similar approaches, suggest a PBL group has 5-8 members, and that practical roles (e.g. Chair, Reader, Timekeeper, Scribe) in addition to scenario specific roles (e.g. Tutor, Student, School Manager) are assigned (Barrett and Moore, 2011). However, the small cohort of six meant that two groups of three were created making it difficult to assign roles – everyone had to do everything, which made things very intense and time consuming for everyone. On reflection, I think it would have been preferable to have one group of six. However, the added (perhaps unnecessary) complication of peer assessing another group’s learning meant that at least two PBL groups needed to be in place.

Also, there were the practical frustrations of varying study schedules (including pressure to work over the Christmas break), and the feelings of there being too much to do, with varying opinion amongst the group on which particular problems/solutions to focus. The scenarios each gave a list of ‘possible topics’ and initially we were trying to un(cover) them all (constrained by a word limit). Once we’d established, with much appreciated guidance from our tutor as ‘facilitator’, that we didn’t need to look at everything, we then seemed to spend too much time discussing which topic to focus on. For example, the scenarios suggested looking at technology-enhanced assessment (TEA), however I was less keen considering this was something I was already familiar with through my own practice, and therefore not an area for my personal development.

Another frustration was in the varying preferences relating to how we were to present the ‘solutions’. I feel that by everyone trying to contribute to the same thing, scenarios became ‘messy’ and ‘inconsistent’ in terms of the writing style, referencing, and media input. Perhaps if we’d have taken the time to identify skills within the team we may have produced something more ‘polished’.

On the positive side, our tutor was a real help, in particular when we had tutor input sessions, which gave us, as a whole cohort, the opportunity to discuss themes related to each scenario across various contexts – science, engineering, life sciences, journalism, education, health and social care. Our tutor was open to what we discussed, whilst also keeping us ‘on track’ if we moved off topic. Looking at the PBL literature that’s exactly the nature of the tutors role – more facilitative – where the focus is on students learning, rather than tutors teaching (Barrett and Moore, 2011) and striking a balance between being dominant and passive – “dominant tutors in the group hinder the learning process, but the quiet or passive tutor who is probably trying not to teach also hinders the learning process” (Dolmans et al., 2005).

During PBL, it is important for the tutor as ‘facilitator’ to ensure adequate time is allocated for constructive feedback throughout the process (Barrett and Moore, 2011). Although our tutor did provide this, it was difficult to agree as a group when we needed the feedback. I would have preferred to grant our tutor access to the three scenarios in-progress from the start, allowing him to provide feedback throughout. However, other group members preferred to wait until nearer the end. I found this quite frustrating, particularly as one aspect of our learning was around the importance of a continuous student-tutor dialogue, and feedback as being formative and ‘developmental’ (HEA, 2012).

Although our tutor shared with us a wealth of knowledge and experiences himself, which was very interesting and useful, he was also more than happy to take a step back and listen to our experiences as practitioners, providing thought provoking statements and questioning – helping us to unravel the scenarios and assisting us in recognising our own wealth of prior knowledge (Barrett and Moore, 2011). In one sense I would have liked more input from our tutor (just because I enjoyed his ‘stories’ so much), however in another sense it was great that he left us to get on with the group-work. As mature practice-based students, we were able to remain relatively motivated, and continued to meet up regularly even when there weren’t any face-to-face sessions. However, I feel this was partly down to there being only three of us – we simply had to get on with it, and there was no room for anyone to take a back seat, even if there were other professional and/or personal commitments. However, I was heartened that having experienced a family bereavement towards the end of the PBL group-work, both my tutor and peers understood that I needed a little time away, although again due the small group I felt pressured (only by myself) to return as soon as possible and get on, so as not to disrupt or delay the group-submission too much.

Despite the challenges I feel that my PBL group worked well together, and at least met the deadline in producing the group’s solutions, and in the end I think we all learnt something, not only about the scenarios themselves and about our collective experience of assessment and feedback practice, but about the potential feelings and frustrations of our students when thrown into similar assessment processes – worthwhile experiential learning (Kolb, 1984).

Aristotle quote

Image Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/abennett96/3374399202/

AFL – the learning journey

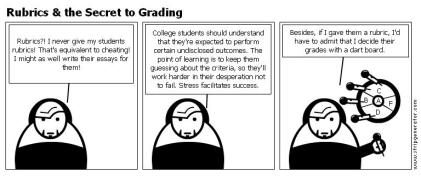

(Cartoon from www.wisepedagogy.com)

PBL1 – What’s in a mark?

(see PBL1 group-submission)

As a staff developer within academic practice, I’m often engaged in discussions with colleagues regarding assessment and feedback. For the most part, I design and facilitate staff development relating to TEL. However, I’ve often felt that I needed to widen my knowledge across various disciplines rather than being limited to my own specialist area, enabling me to better support and advise my colleagues. For example, a recent strategic initiative to roll out e-Assessment institution-wide has lead to staff development in this area, including the use of e-Submission and e-Marking/e-Feedback tools. Throughout, I’ve met with some resistance towards the use of electronic rubrics, which seemed to stem from a general resistance to the use of rigid criteria and standards – whether paper-based or electronic.

The PBL1 group-work and related tutor input sessions helped me to take a step back and reflect on why my academic colleagues held such strong often negative views on the development and use of assessment criteria linked to learning outcomes. My own views were relatively positive, with a view that such standards provided transparency for both students and tutors in terms of what was being assessed and how. How could anyone argue with that?

Throughout the initial weeks on AFL, I soon began to further understand where these negative viewpoints came from, and a lot had to do with changing HE systems and structures. In the old days of University education, when the opportunity for furthering education through HE was restricted to an elite few, the University experience was very different. The ‘academic’ was deemed as the all-knowing authority, learning was ‘passive’ – a transfer of knowledge from the expert to the novice, with a focus on the acquisition of expert-knowledge, rather than experience or skill. Transferring from this to the current culture, where there is an increased and diverse student body paying high fees as ‘customers’, where students and tutors are deemed as partners in learning, and where learning is ‘active’ providing opportunity for students to co-construct their own knowledge collaboratively through both theory and practice (HEA, 2012). In terms of assessment and feedback there was more scope for individual ‘academic’ subjectivity, however today HE institutions are under the scrutiny of the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) to ensure consistent and transparent assessment and feedback practices (QAA, 2011).

This has lead to a perceived obsession with bureaucratic processes linked with compliance and standards – learning outcomes, criteria – rather than there being a focus on ‘learning’ which some believe is lost through the bureaucracy. Furedi (2012) in his article ‘The unhappiness principle’ argues that learning outcomes “disrupt the conduct of the academic relationship between teacher and student”, “foster a climate that inhibits the capacity of students and teachers to deal with uncertainty”, “devalues the art of teaching”, and “breeds a culture of cynicism and irresponsibility”. The article certainly sparked some debate, some of which we talked about on AFL. How can we prescribe outcomes, when learning for everyone is different depending on where they start from in the first place, and indeed where they intend to go? Can, or should, we actually guarantee anything as an outcome of learning? Can the presence of outcomes as a ‘check list’ of learning discourage from creativity, exploration, and discovery in learning? Or, does the absence of learning outcomes provide a ‘mystic’ that encourages creativity, exploration, and discovery? Does such ‘mystic’ foster deeper learning or merely confusion and student dissatisfaction?

Through collaborative exploration during both the PBL group-work and discussions with the whole cohort, it was clear that to some degree consistency, transparency, and constructive alignment of assessment criteria with learning outcomes are important factors, not just to satisfy QAA requirements, but also to ensure validity, reliability and fairness to both tutors and students as partners in learning (University of Salford, 2012). It is also important to acknowledge and respect that there will always be an element of subjectivity, as responsibility for marking is largely down to the subjective judgement of tutors and other markers (Bloxham and Boyd, 2007).

In terms of where this relates to my own practice, I feel the conclusions are relevant in that I need to work with academic colleagues to further understand their assessment and feedback practices. During AFL I came across some real examples of criteria and/or rubrics in-practice at Salford, which although not fully aligned with University guidance (e.g. use of A-F grades), they do seem to work in that staff, students, and external examiners have praised some of the practice. As a staff developer I need to appreciate and fully understand current practice, and work with colleagues to facilitate a ‘community’ amongst programme and subject teams to enable them to work collectively, socially constructing a set of shared standards to ensure valid, reliable, and fair assessment and feedback practice.

PBL2 – Where’s my feedback, dude?

(see PBL2 group-submission)

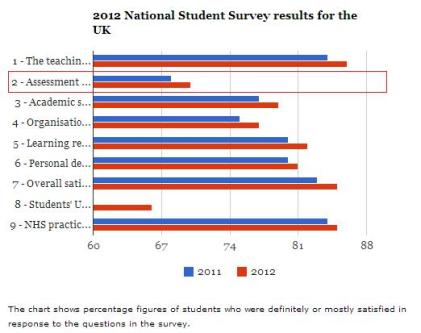

Although as a PBL group all three of us contributed to each scenario, PBL2 was where I contributed much of the initial literature searches and writing, perhaps because I saw this particularly scenario as most relevant to my current practice. Recently, I have been working closely with academic colleagues to try and unravel why assessment and feedback continues to be an area of lower student satisfaction than in any other area, both locally within the institution and nationally across UK HE (HEA, 2012; HEFCE, 2012).

Before my PBL group could effectively start to look at current practice, it was useful to take a step back and reflect upon what changes in HE may have impacted on how staff and students perceive assessment and feedback. As a relatively ‘young’ learner, I have experienced a ‘modular’ University education (1997-present), and as such hadn’t really thought extensively about University education pre-1990s, and particularly how the introduction of a modular system created a significant growth in summative assessment (HEA, 2012). This certainly echoes some of the opinions of colleagues who speak about over-assessing, and resonates with some of the recent changes in policy – a move from 15 to 30 credit modules.

Also, a common response to the poor performance in the National Student Survey (NSS) is that students don’t realise when they’re receiving feedback (Boud, 2012). At one time I may have gone along with this simplistic viewpoint, however through exploration of the PBL2 scenario, I have developed my understanding and ideas around how institutions can start to address the issues surrounding assessment and feedback.

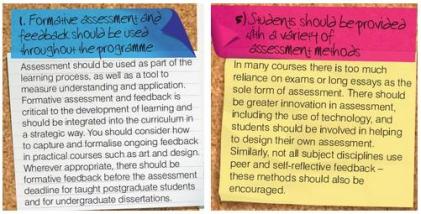

Research suggests that improvements in assessment and feedback can be achieved through reviewing practice, making changes to course and curriculum design, and questioning – what is feedback?, and how is it useful? (Boud, 2012). Timely and developmental feedback, ensuring students are able to act on feedback to develop future work, are key factors and align with research on ‘assessment for learning’ (Biggs, 1996: Gibbs & Simpson, 2004; 2005, Walker, 2012), as opposed to ‘assessment of learning’.

Another important factor for improvement is ensuring a continuous dialogue to facilitate development, and whilst there is a preference for more personal contact between student and tutor (Gibbs, 2010), there is also a need to provide more opportunity for dialogue between students themselves, and to involve them as partners in learning and in deciding how they are assessed. Within my PBL group, peer-assessment, as an active teaching and learning approach, was explored as one way of achieving this (Falchikov, 1995; 2005; Fry, 1990; Hughes, 2001; Orsmond, 2004).

Of the staff development sessions I’ve facilitated relating to assessment and feedback as part of my practice and during the PGCAP (see post Reflection 4/6 – Tutor observation), due to the element of ‘poor performance’ in the NSS linked to discussion, I have sometimes found them uncomfortable and intense sessions. I feel that working with my PBL group in a relaxed shared ‘learning’ environment has enabled further exploration of varied practice, strengthening my ability and confidence to facilitate these sessions in the future.

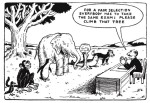

(Cartoon from http://ginacarson.com/ud/universal-design/)

PBL3 – A module assessment redesign

(see PBL3 group-submission)

PBL3 was unlike the others, in that the group had to agree upon an area of practice where an assessment redesign was necessary, and use the scenario of a seemingly unfair assessment to inform the redesign. All group members had ideas for redesign from various contexts, however it was decided to focus on the redesign of a module in mechanical engineering as this linked with aspects of ‘authentic’ and ‘negotiated’ assessment, which seemed most relevant to ‘inclusive’ assessment and the scenario.

Through exploring these areas to inform the redesign, I have developed my understanding of inclusive assessment and feedback practice both in terms of enabling (1) authentic assessment which reflects ‘real-world’ practice, and (2) negotiated assessment relating to choice of assessment topic, learning outcomes/criteria, or the medium in which the student presents their learning.

The redesign of the mechanical engineering module to enable students to experience the practical elements of testing individual systems was one way of achieving authenticity, as is providing work experience and placement opportunities. Programmes and modules, such as in health and social care, are examples of where authenticity is central to learning. On the PGCAP, students engage in teaching observations providing an insight for learners into professional practice across various disciplines. However, these examples either require money and/or a working partnership with employers or an established practice-based approach.

“As increasing numbers of students enter higher education with the primary hope of finding employment, there is a pressure to ensure that assessment can, at least in part, mirror the demands of the workplace or lead to skills that are relevant for a range of ‘real world’ activities beyond education, but this has been largely unreflected in the reform of assessment within many disciplines” (HEA, 2012).

As someone who has always studied part-time whilst working full-time in an area directed related to study, I’ve had the opportunity to link theory with practice. However, I often reflect on how those undergraduate students studying full-time without work experience manage to apply their knowledge to practice with a view to improving their employability.

Therefore, my personal interest is around what methods foster an authentic learning experience, where without the budget to buy expensive kit or provide placements, authentic assessment can still be achieved. Interestingly, PBL is one such method where students are provided real-world authentic problems to work on in groups, tasked to produce a collaborative report as an authentic assessment task. This provides authenticity not only relating to the problems themselves, however also relating to the skills required to work within the group – problem-solving, teamwork, communication, time management, presentation of work in various formats – all skills of value to the employer (Bloxham and Boyd, 2007).

The aspect of ‘negotiated learning’ was also of interest. By providing students with the opportunity to negotiate their own learning path through choice of learning outcomes, assessment criteria, topic, or format students become involved, taking responsibility for their own learning and assessment (Boud, 1992). I have in the past been involved in negotiated learning where, as in the mechanical engineering module redesign the negotiation was linked to the choice of topic (e.g. ALT module), however the concept of taking this further enabling students to negotiate learning outcomes and/or assessment criteria is an area which I’d like to explore further to inform future practice. The PBL3 group exploration of the use of assessment schedules or ‘learning contracts’ is a spring-board to further reading in this area.

“The negotiated learning contract is potentially one of the most useful tools available to those interested in promoting flexible approaches to learning. A learning contract is able to address the diverse learning needs of different students and may be designed to suit a variety of purposes both on course and in the workplace” (Anderson and Boud, 1996).

Although the final group-submission of the scenarios weren’t as ‘polished’ as I’d liked, and in the end I had to ‘let go’, I do feel that the learning journey as a whole has benefited me hugely in terms of ‘sharing’ and constructing ‘new knowledge’, which has helped me to achieve my learning goals. I feel more able to support my colleagues in their wider academic practice relating to assessment and feedback, and more confident in my own assessment and feedback practice as a module tutor. Time and ‘experience’ will tell!

Action plan

- Staff development (Colleges) – Work with programme teams and/or subject areas to facilitate a ‘community’ and sharing of assessment and feedback practices, aiming towards developing a shared set of standards.

- Module tutor (PGCAP) – Work with PGCAP programme team, developing my own assessment and feedback practices through becoming part of a ‘community’ and sharing of assessment and feedback practices, aiming towards developing a shared set of standards.

- CPD (AFL) – Further develop my understanding of assessment and feedback practices by further reading and co-facilitating AFL in the future, having the opportunity to listen to more ‘stories’ of colleagues from various contexts across the University.

- CPD (PBL) – Further develop my own PBL practice by further reading and as a PBL ‘facilitator’ on the AFL module, and participate as a learner on the Flexible, Distance and Online Learning (FDOL) open course to continue the PBL student experience, however in an online and global context.

References

Anderson, G. and Boud, D. (1996) Introducing Learning Contracts: A Flexible Way to Learn.

Innovations in Education & Training International Vol. 33, Iss. 4, 1996. Available online http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1355800960330409 (accessed Jan 2013).

Barrett, T. and Cashman, D. (Eds) (2010) A Practitioners’ Guide to Enquiry and Problem-based Learning. Dublin: UCD Teaching and Learning. Available online http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/ucdtli0041.pdf (accessed Jan 2013).

Barrett, T. and Moore, S. (2011) New approaches to problem-based learning: revitalising your practice in higher education. New York, Routledge.

Biggs, J. (1996) Assessing learning quality: reconciling institutional, staff and educational demands. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 12(1): 5-15. Available online http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0260293960210101(accessed Jan 2013).

Bloxham, S. and Boyd, P. (2007) Developing Effective Assessment in Higher Education: A Practical Guide. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Boud, D. (1992) The Use of Self-Assessment in Negotiated Learning. Available online http://www.iml.uts.edu.au/assessment-futures/subjects/Boud-SHE92.pdf

Boud, D. (2012) A transformative activity. Times Higher Education (THE). 6th September 2012. Available online http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?sectioncode=26&storycode=421061 (accessed Jan 2013).

Dolmans, D. H. J. M., De Grave, W., Wolfhagen, I. H. A. P. and Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2005), Problem-based learning: future challenges for educational practice and research. Medical Education, 39: 732–741. Available online http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02205.x/full (accessed Jan 2013).

Falchikov, N. (2003) Involving Student in Assessment, Psychology Learning and Teaching, 3(2), 102-108. Available online http://www.pnarchive.org/docs/pdf/p20040519_falchikovpdf.pdf (accessed Jan 2013).

Falchikov, N. (1995) Peer feedback marking: developing peer assessment, Innovations in Education and Training International, 32, pp. 175-187.

Fry, S. (1990) Implementation and evaluation of peer marking in Higher Education. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 15: 177-189.

Gibbs, G. & Simpson, C. (2004) Conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning, Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 1. pp.1-31. Available online http://www2.glos.ac.uk/offload/tli/lets/lathe/issue1/issue1.pdf#page=5(accessed Jan 2013).

Gibbs, G. & Simpson, C. (2005) Does your assessment support your students’ learning? Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1. Available online http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.201.2281&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed Jan 2013).

Gibbs, G. (2010) Dimensions of quality. Higher Education Academy: York. Available online http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/documents/evidence_informed_practice/Dimensions_of_Quality.pdf (accessed Jan 2013)

Gibbs G (1988) Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford.

HEA (2012) A Marked improvement: Transforming assessment in higher education, York, Higher Education Academy. Available online http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/resources/detail/assessment/a-marked-improvement (accessed Jan 2013).

HEFCE (2012) National Student Survey. Available online http://www.hefce.ac.uk/whatwedo/lt/publicinfo/nationalstudentsurvey/ (accessed Jan 2013).

Hughes, I. E. (2001) But isn’t this what you’re paid for? The pros and cons of peer- and self-assessment. Planet, 2, 20-23. Available online http://www.gees.ac.uk/planet/p3/ih.pdf (accessed Jan 2013).

Furedi, F. (2012) The unhappiness principle. Times Higher Education (THE). 29th November 2012. Available online http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=421958 (accessed Jan 2013)

Kolb, D. (1984) Experiential Learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gibbs G (1988) Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford.

Moon J. (2004) A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning, Routledge Falmer.

Orsmond, P. (2004) Self- and Peer-Assessment: Guidance on Practice in the Biosciences, Teaching Bioscience: Enhancing Learning Series, Centre for Biosciences, The Higher Education Academy, Leeds. Available online http://www.bioscience.heacademy.ac.uk/ftp/teachingguides/fulltext.pdf (accessed Jan 2013).

QAA (2011) Quality Code – Chapter B6: Assessment of students and accreditation of prior learning. Available online http://www.qaa.ac.uk/Publications/InformationAndGuidance/Pages/quality-code-B6.aspx (accessed Jan 2013).

University of Salford (2011) Transforming Learning and Teaching: Learning & Teaching Strategy 2012-2017. Available online http://www.hr.salford.ac.uk/employee-development-section/salford-aspire (accessed Jan 2013).

University of Salford (2012) University Assessment Handbook: A guide to assessment design, delivery and feedback. Available online http://www.hr.salford.ac.uk/cms/resources/uploads/File/UoS%20assessment%20handbook%20201213.pdf (accessed Jan 2013).

Walker, D. (2012) Food for thought (20): Feedback for learning with Dr David Walker. Available online http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNu3fMMNQlw (accessed Jan 2013).

Filed under: -PGCAP, -PGCAP AFL, -PGCAP Assessment, A0-Areas of Activity, A1-learning activities, A2-supporting learning, A3-assessment-feedback, A4-learning environments, A5-research & sholarship, K0-Core Knowledge, K1-subject, K2-T&L methods, K3-student learning, K4-learning technologies, K5-evaluation methods, K6-QA/QE in teaching, V0-Professional Values, V1-diverse learners, V2-equality for learners, V3-evidence-informed, V4-wider HE context | Tagged: AFL theory, assessment & feedback, constructive alignment, course design, experiential learning, feedback, formative assessment, inclusive assessment, inclusivity, learning theories, literature, moderating, peer assessment, problem-based learning, summative assessment, teaching and learning, technology, tel | Leave a comment »